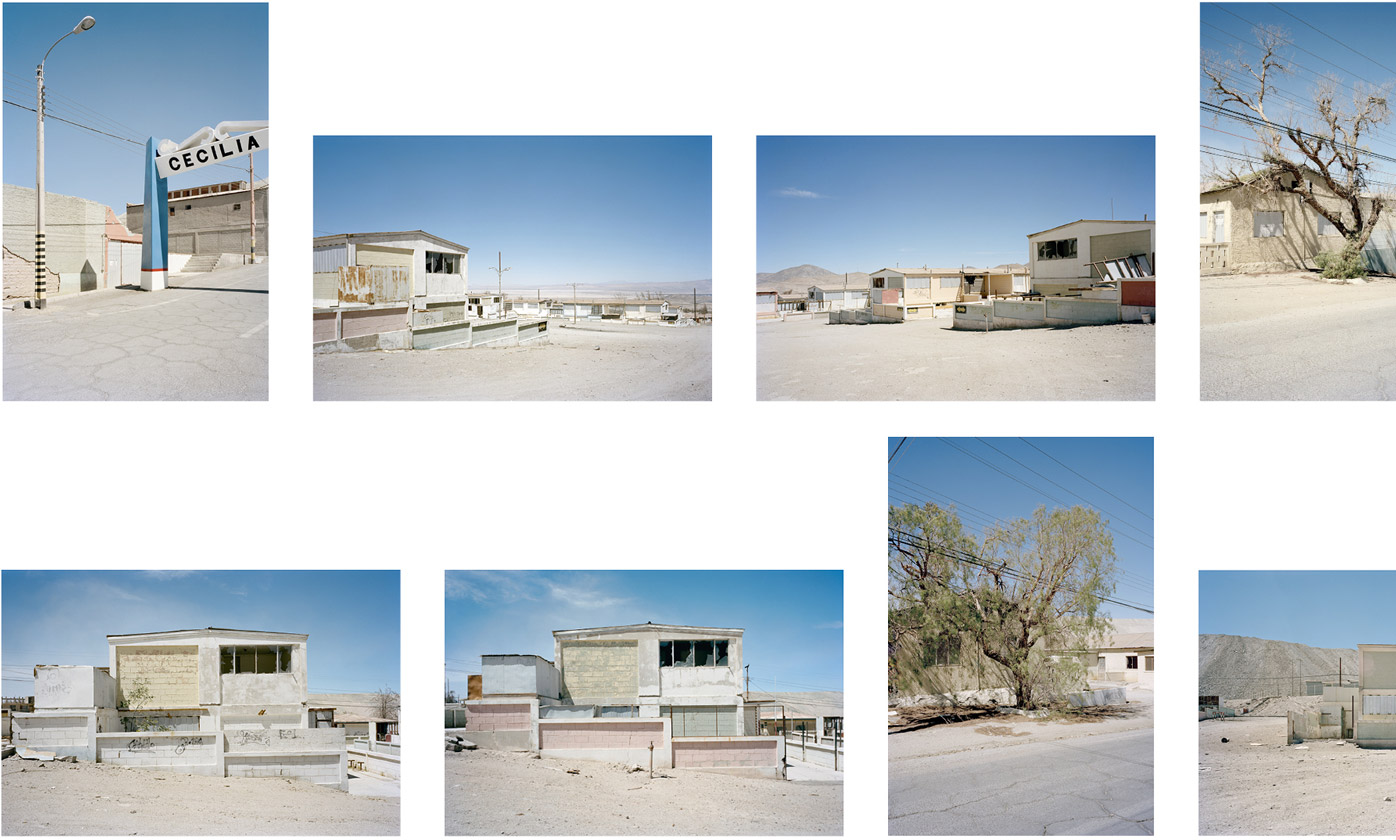

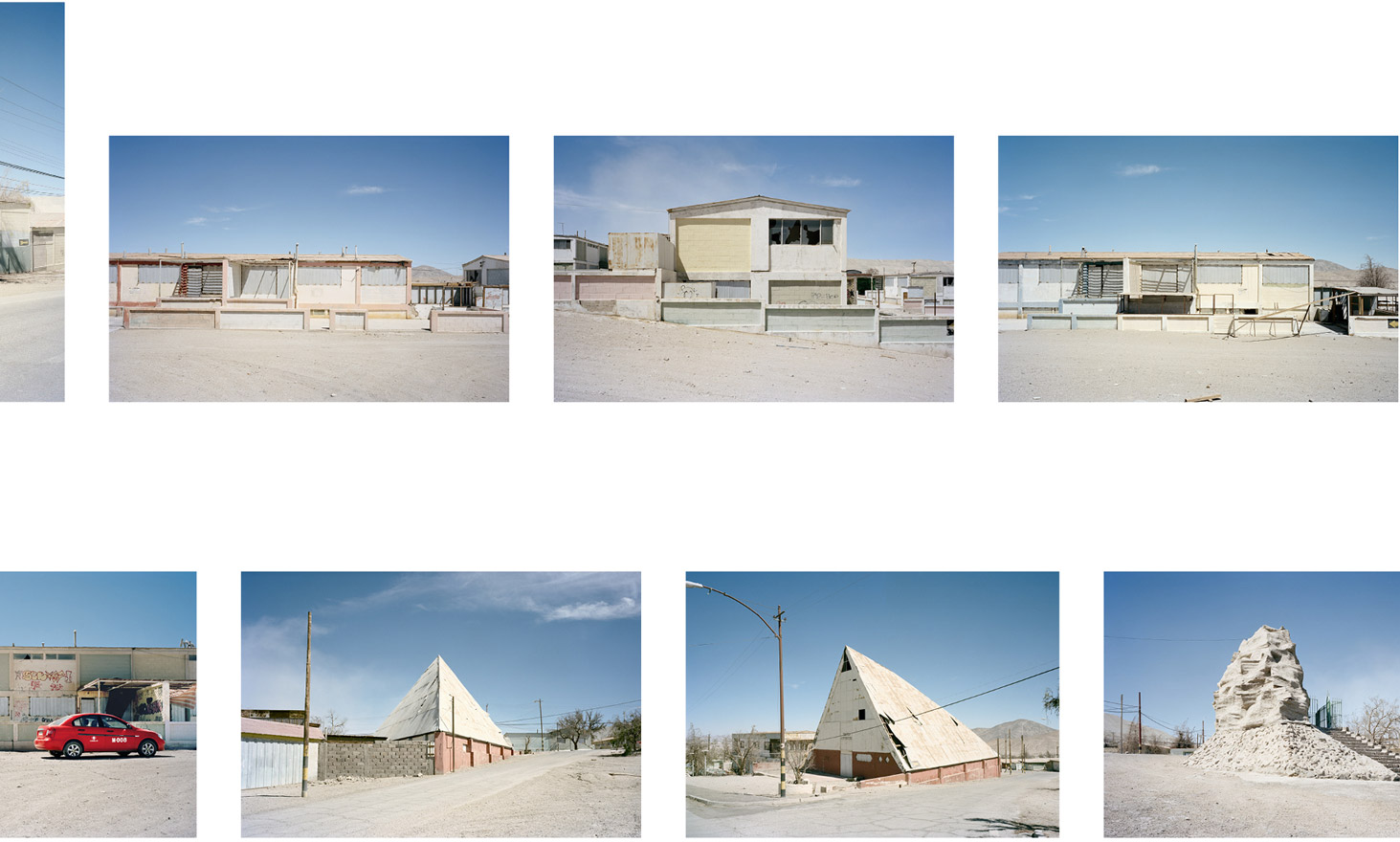

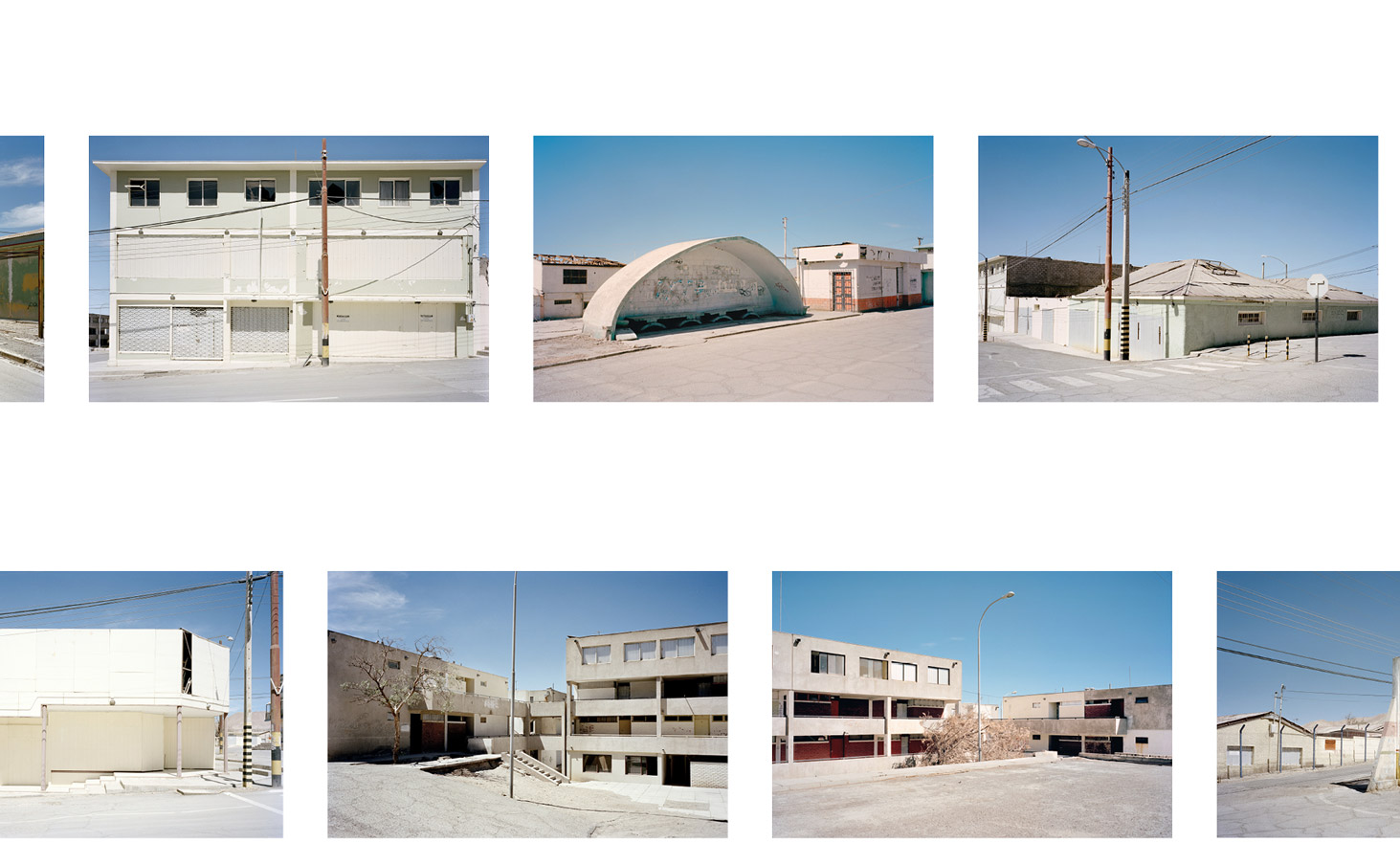

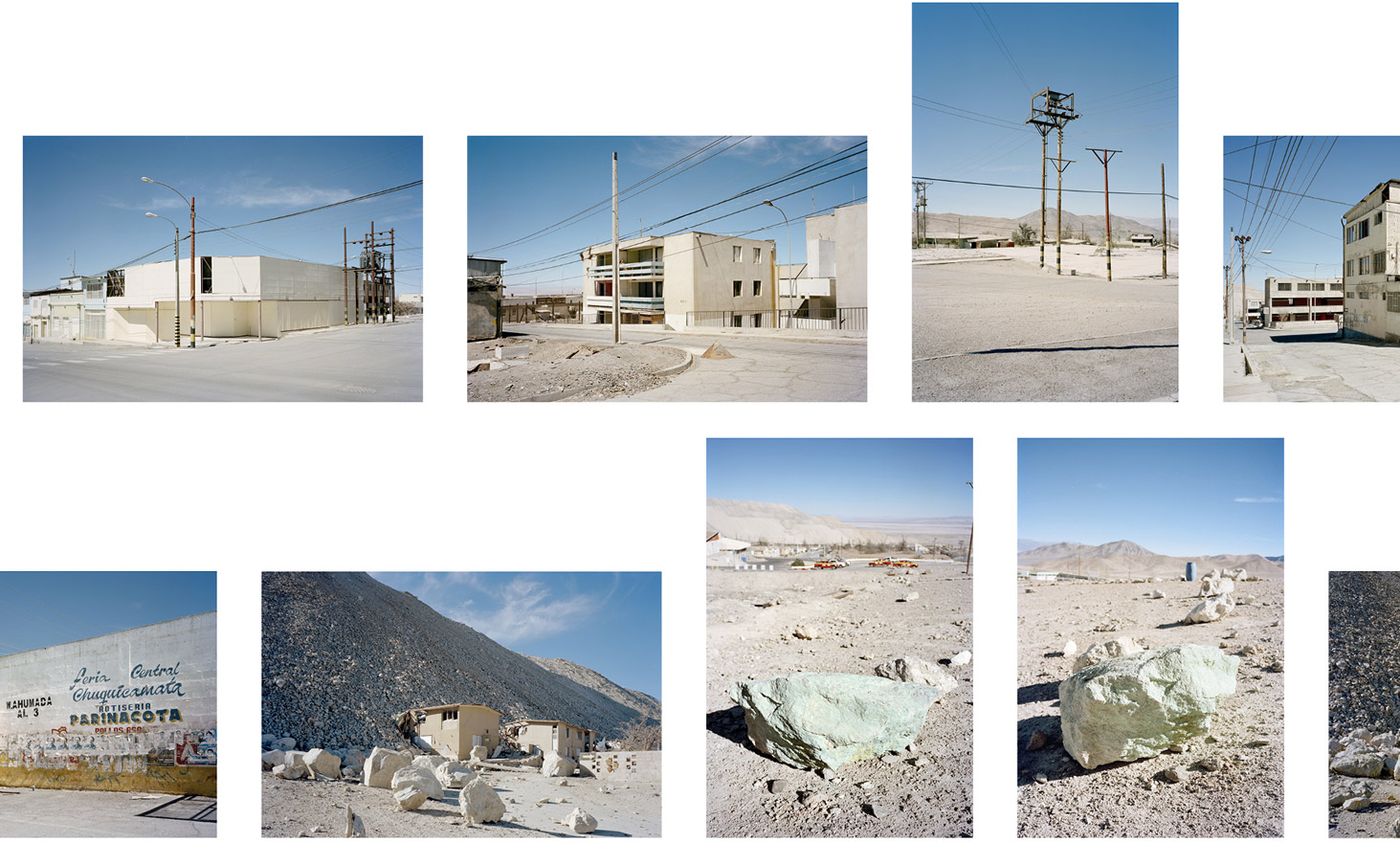

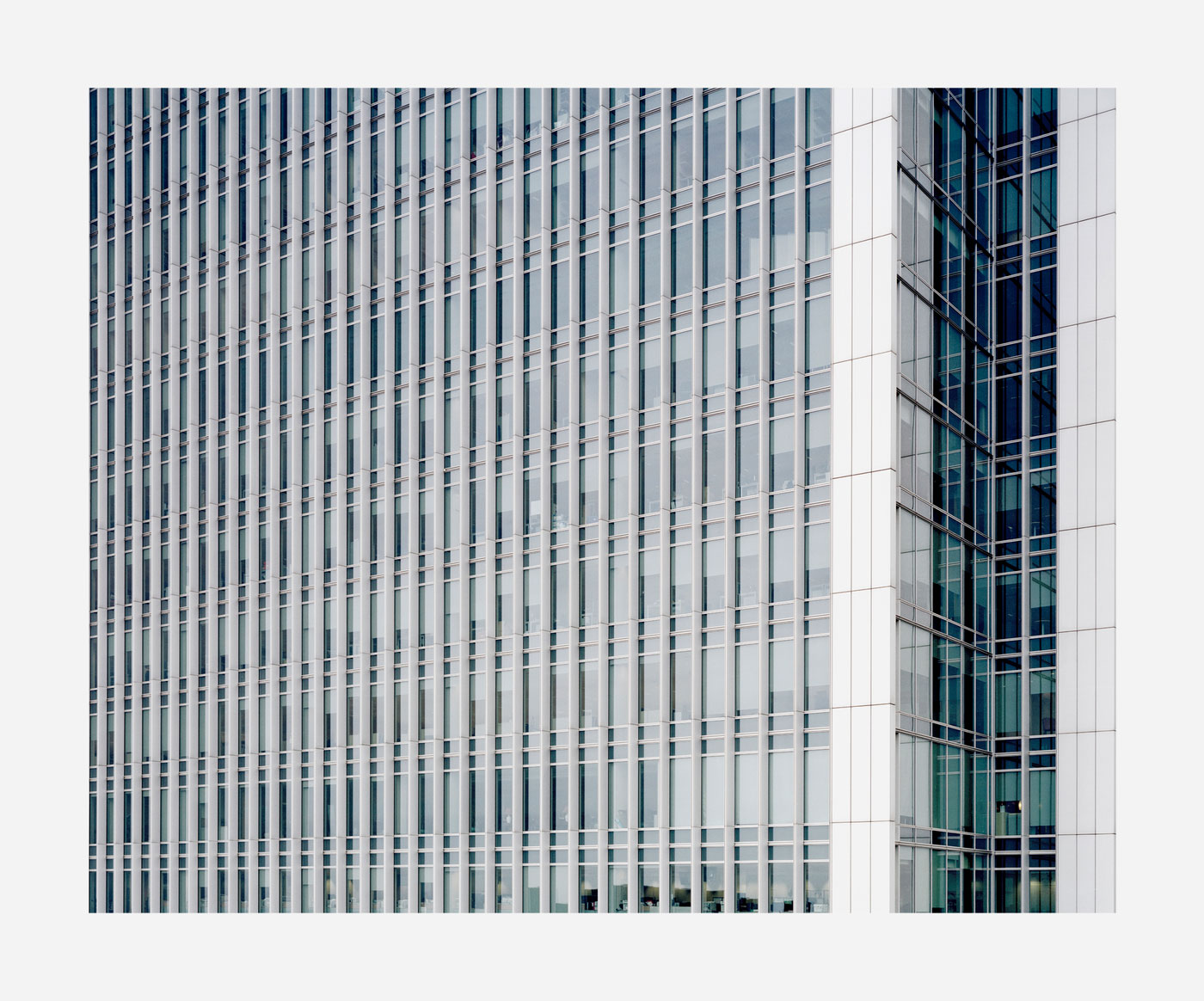

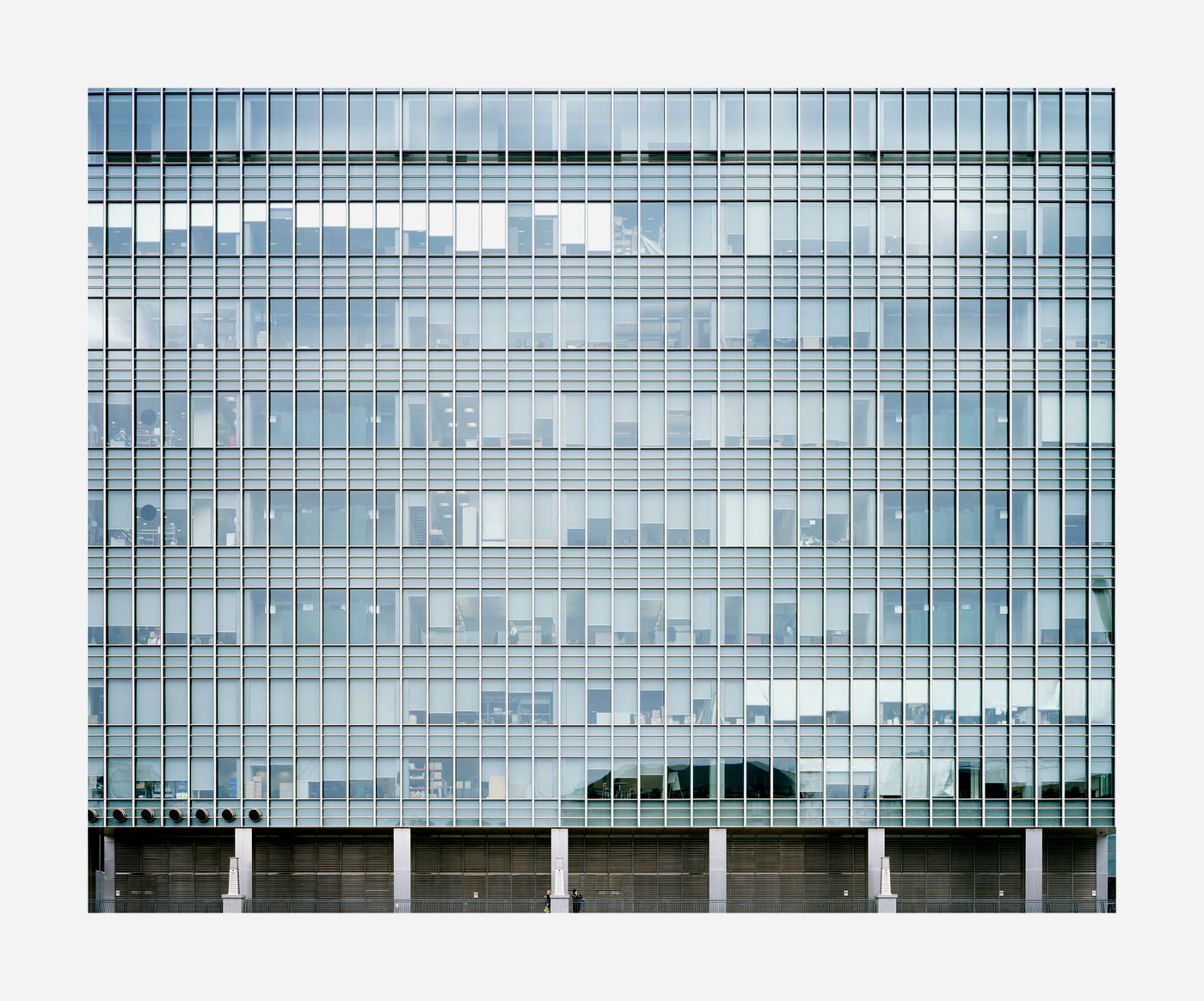

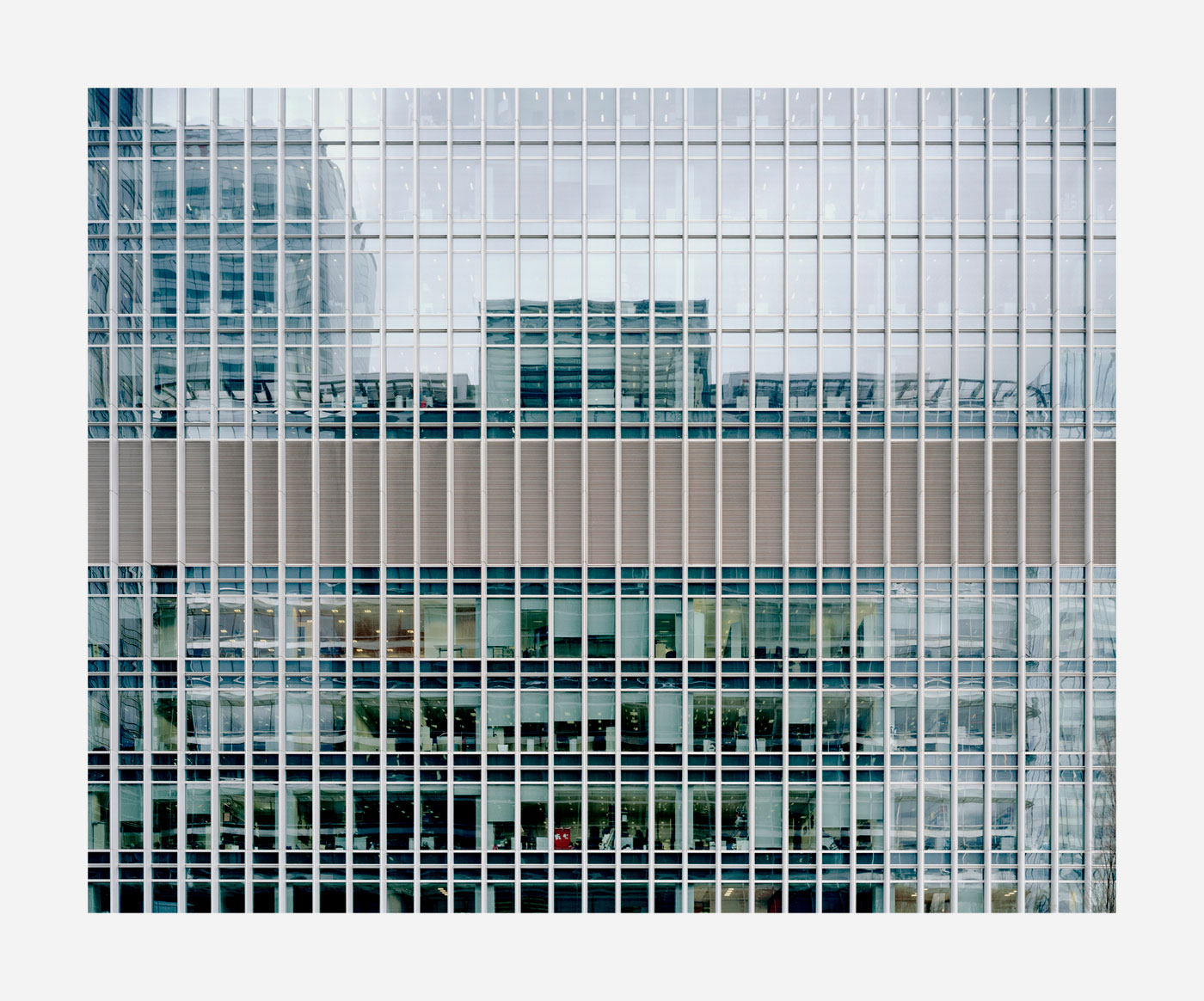

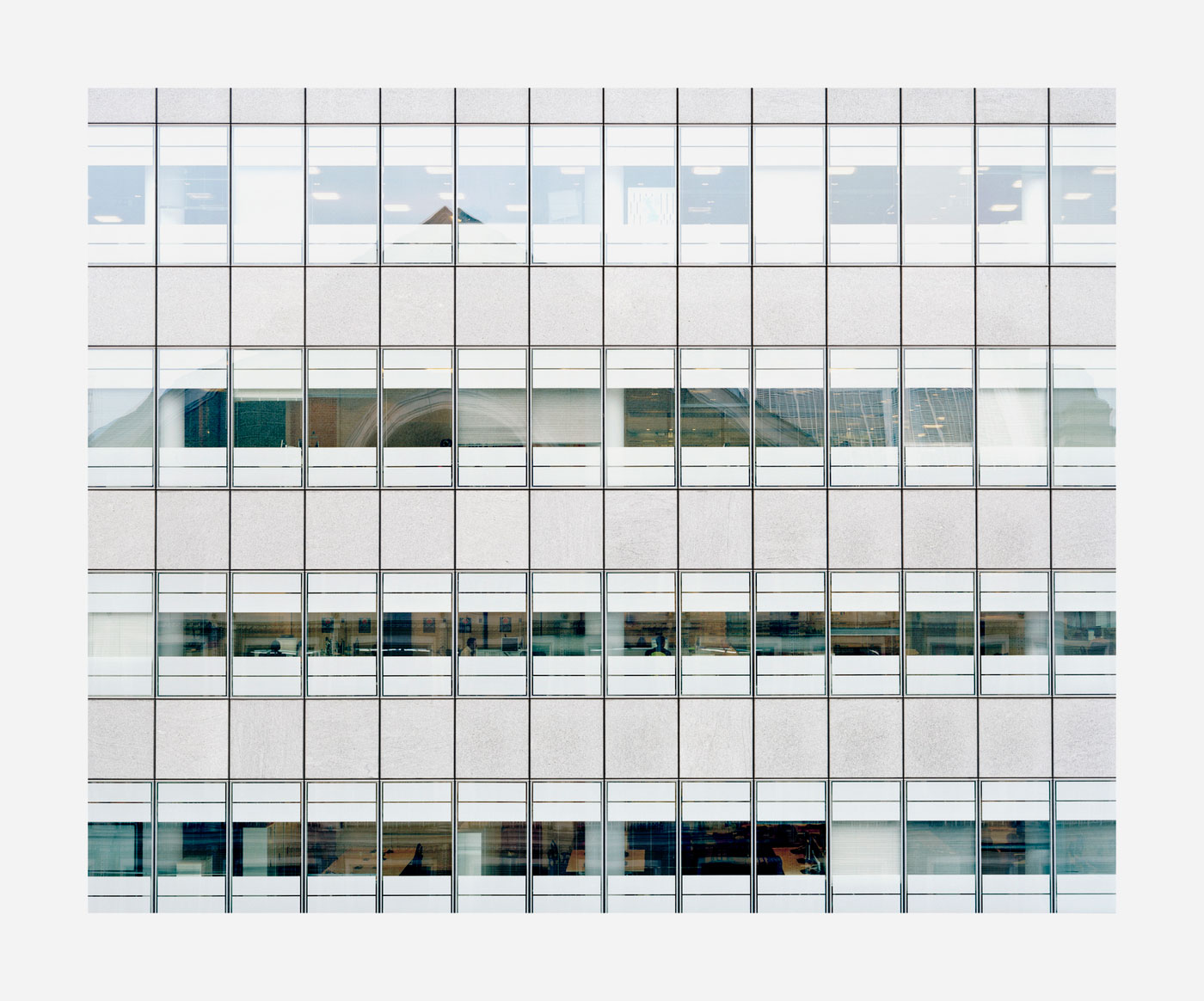

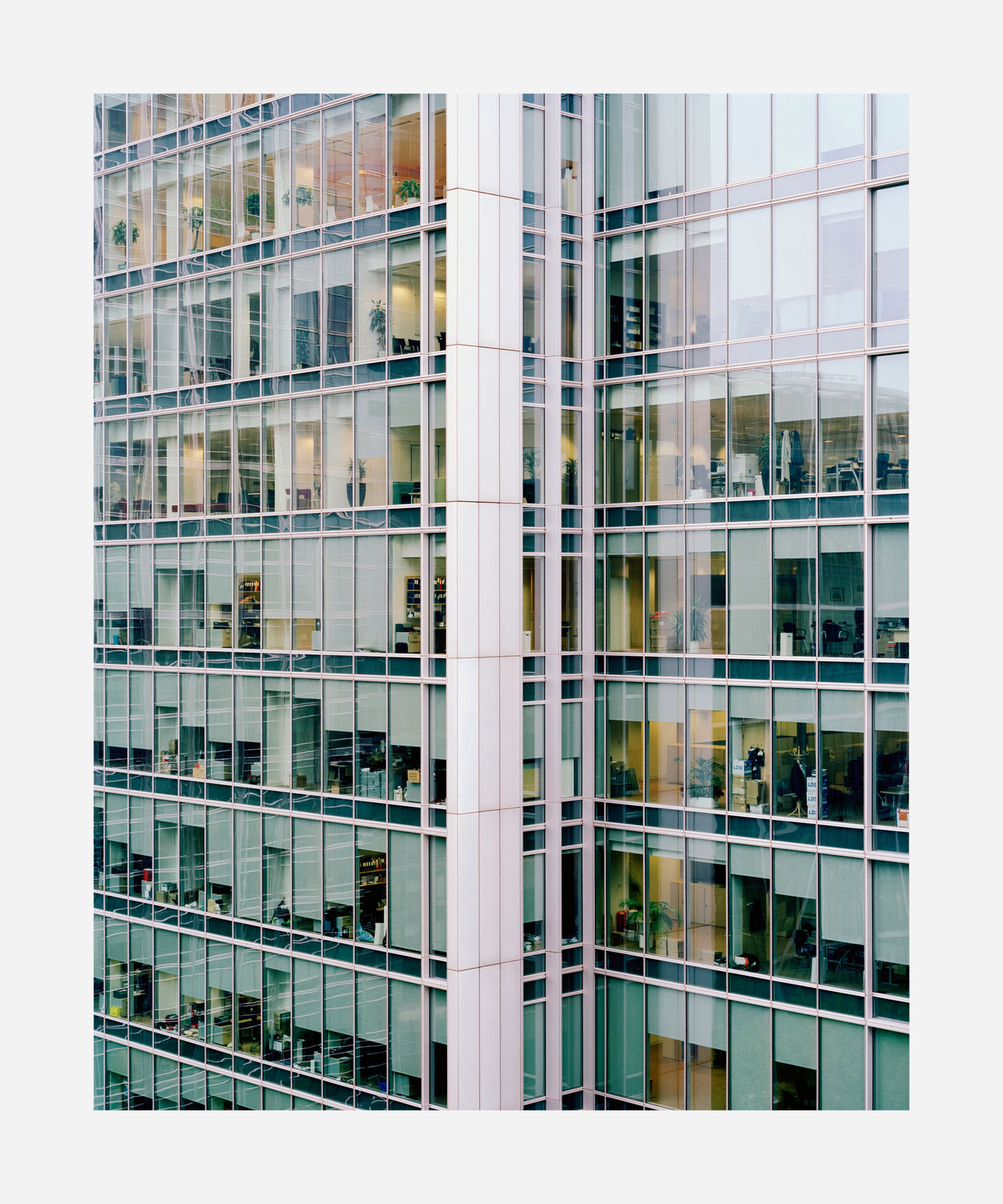

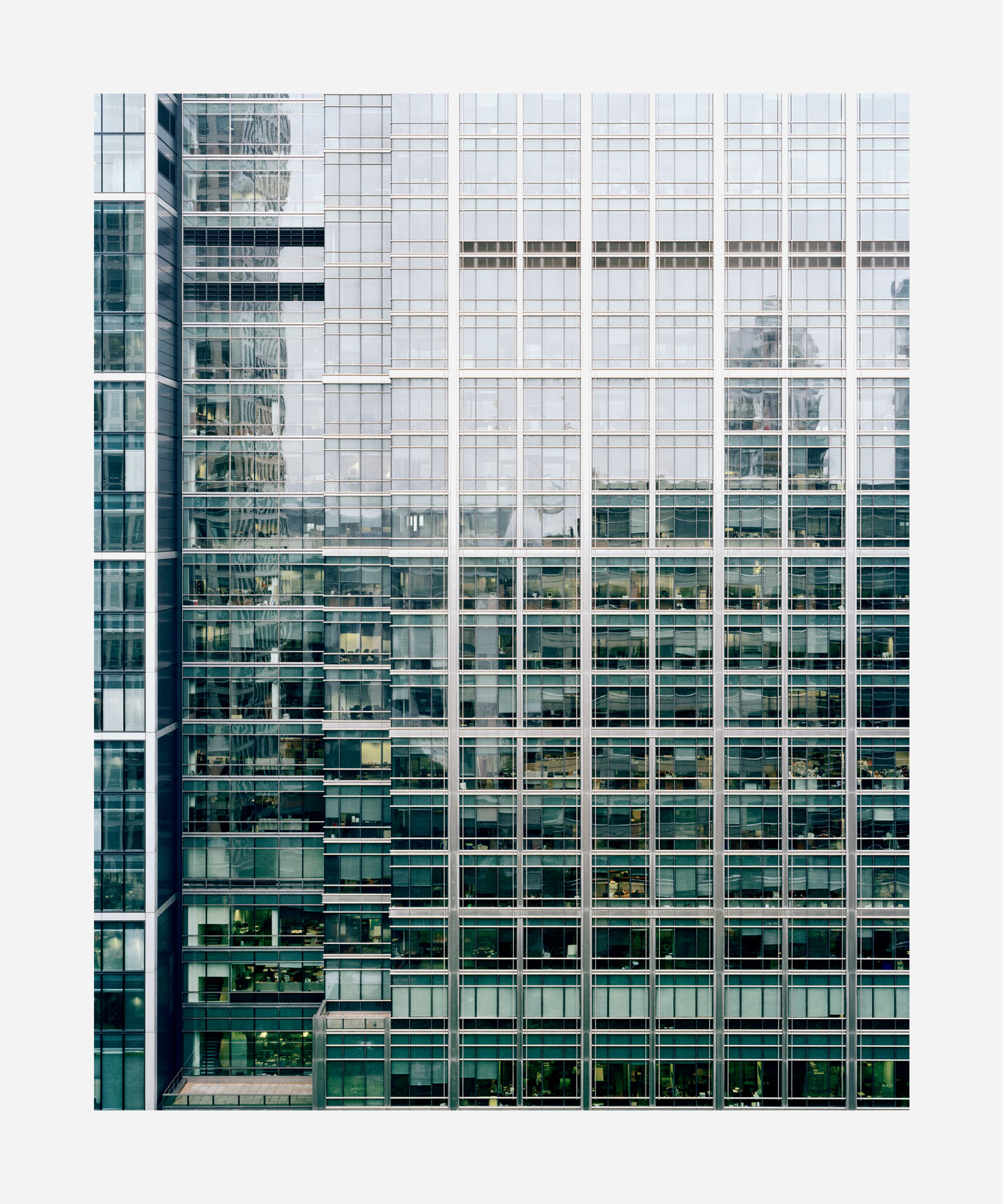

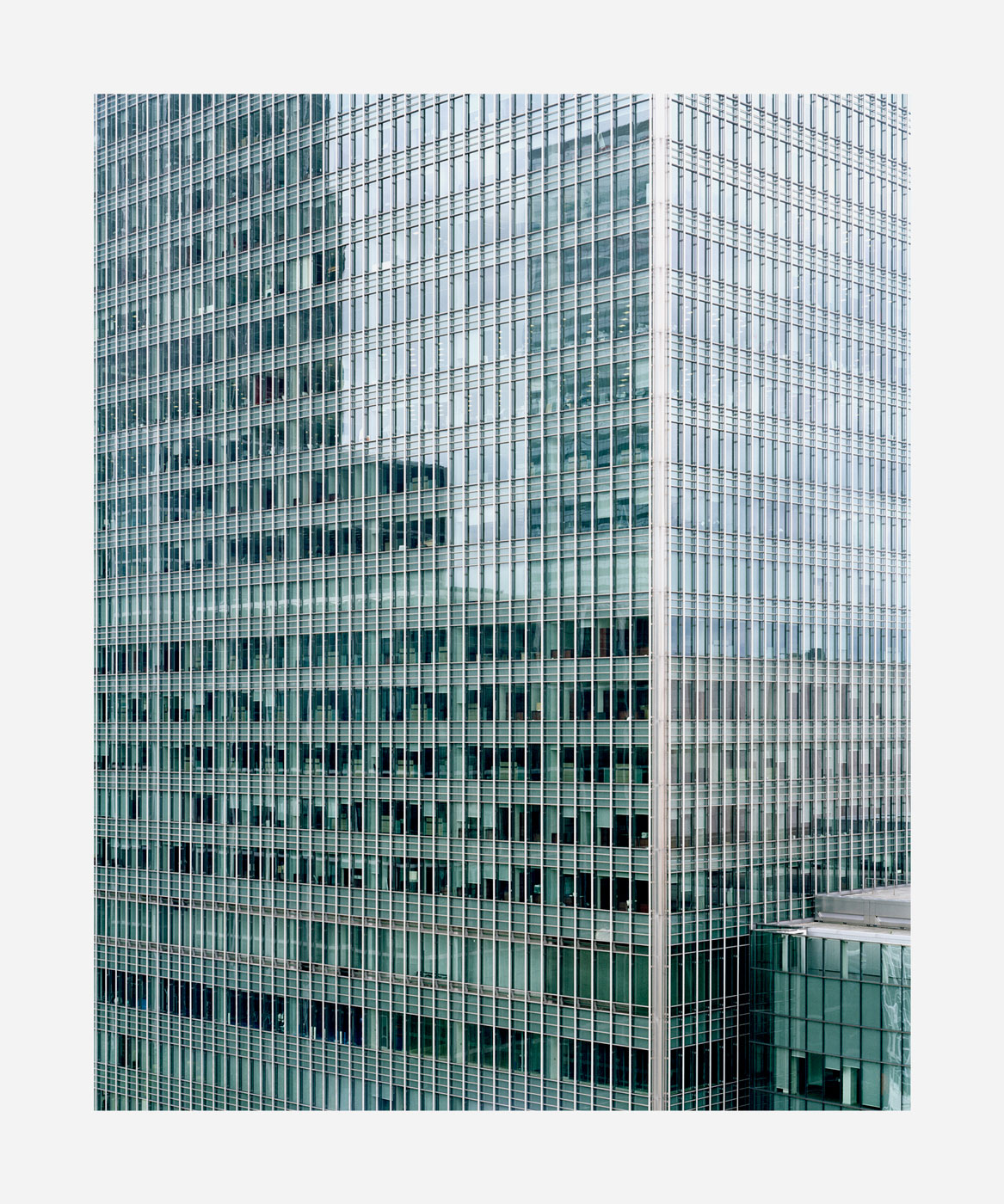

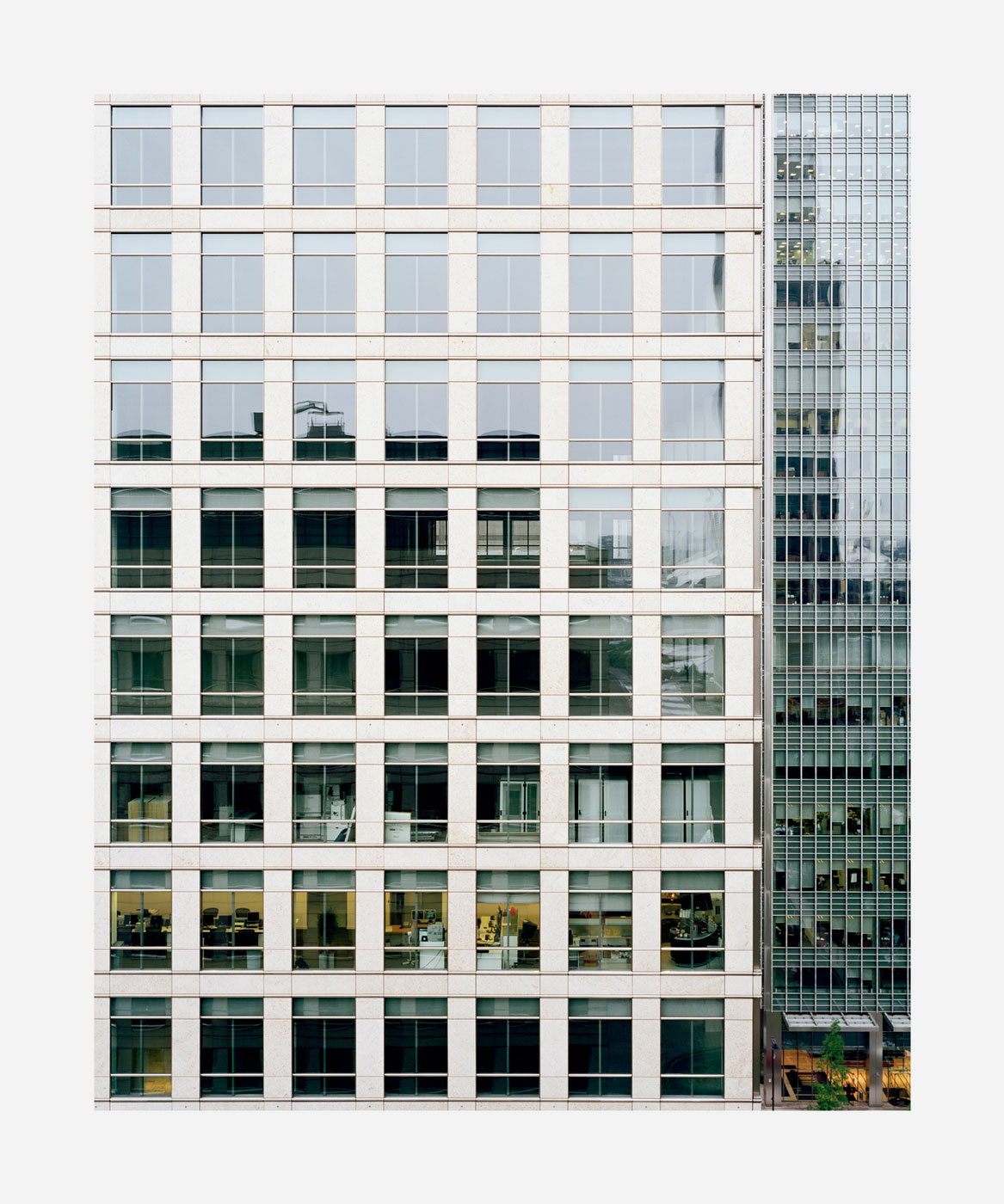

Copper objects and interior decor at Sudley House, home of one of Liverpool’s finest painting collections, assembled by George Holt (1825-1896), who made his fortune in the trade of copper ore and other raw materials. Liverpool, England, 2015

Copper objects and interior decor at Sudley House, home of one of Liverpool’s finest painting collections, assembled by George Holt (1825-1896), who made his fortune in the trade of copper ore and other raw materials. Liverpool, England, 2015

Copper objects and interior decor at Sudley House, home of one of Liverpool’s finest painting collections, assembled by George Holt (1825-1896), who made his fortune in the trade of copper ore and other raw materials. Liverpool, England, 2015

Copper objects and interior decor at Sudley House, home of one of Liverpool’s finest painting collections, assembled by George Holt (1825-1896), who made his fortune in the trade of copper ore and other raw materials. Liverpool, England, 2015

Copper objects and interior decor at Sudley House, home of one of Liverpool’s finest painting collections, assembled by George Holt (1825-1896), who made his fortune in the trade of copper ore and other raw materials. Liverpool, England, 2015

Copper objects and interior decor at Sudley House, home of one of Liverpool’s finest painting collections, assembled by George Holt (1825-1896), who made his fortune in the trade of copper ore and other raw materials. Liverpool, England, 2015

Copper objects and interior decor at Sudley House, home of one of Liverpool’s finest painting collections, assembled by George Holt (1825-1896), who made his fortune in the trade of copper ore and other raw materials. Liverpool, England, 2015

Copper objects and interior decor at Sudley House, home of one of Liverpool’s finest painting collections, assembled by George Holt (1825-1896), who made his fortune in the trade of copper ore and other raw materials. Liverpool, England, 2015

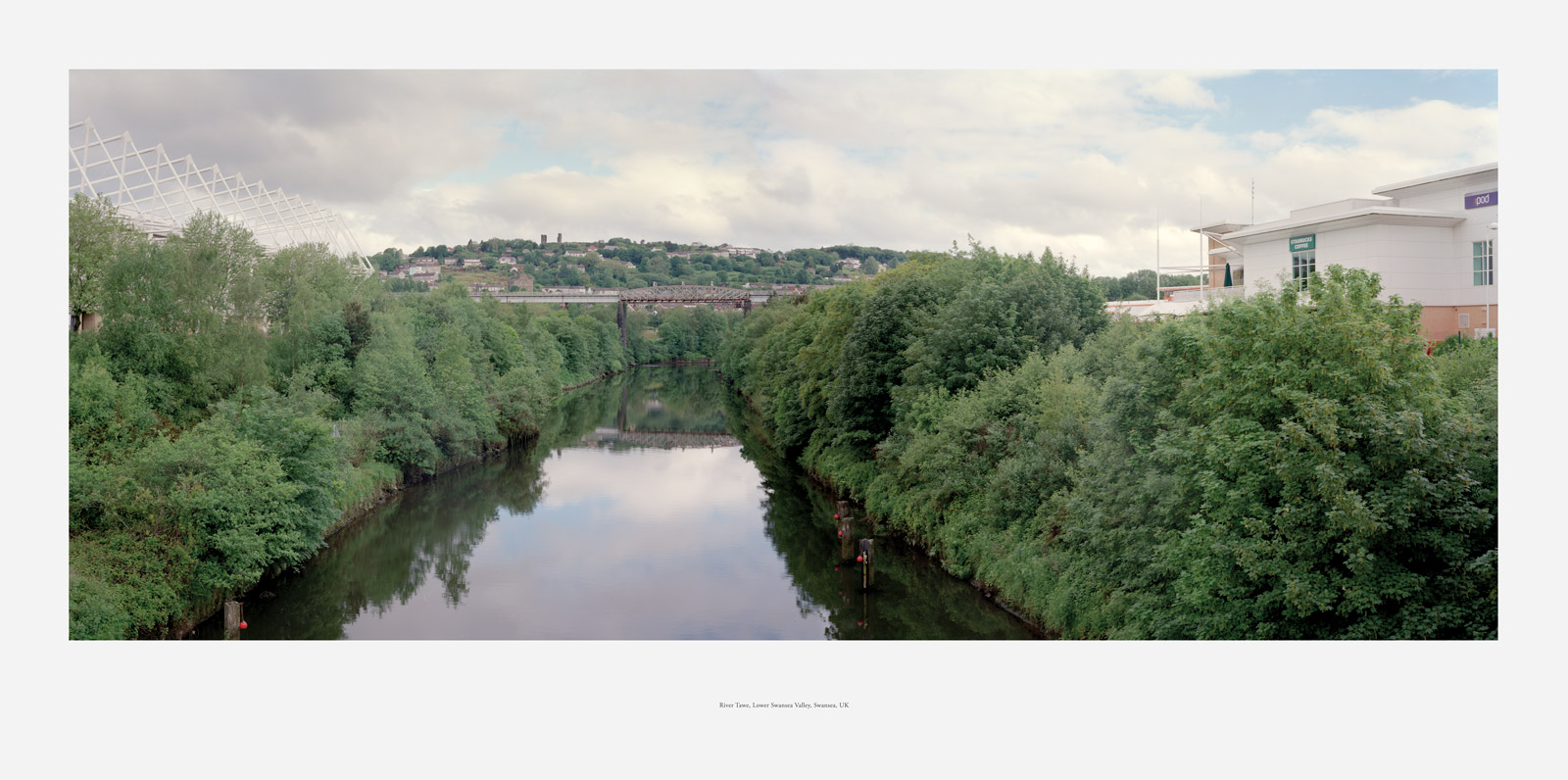

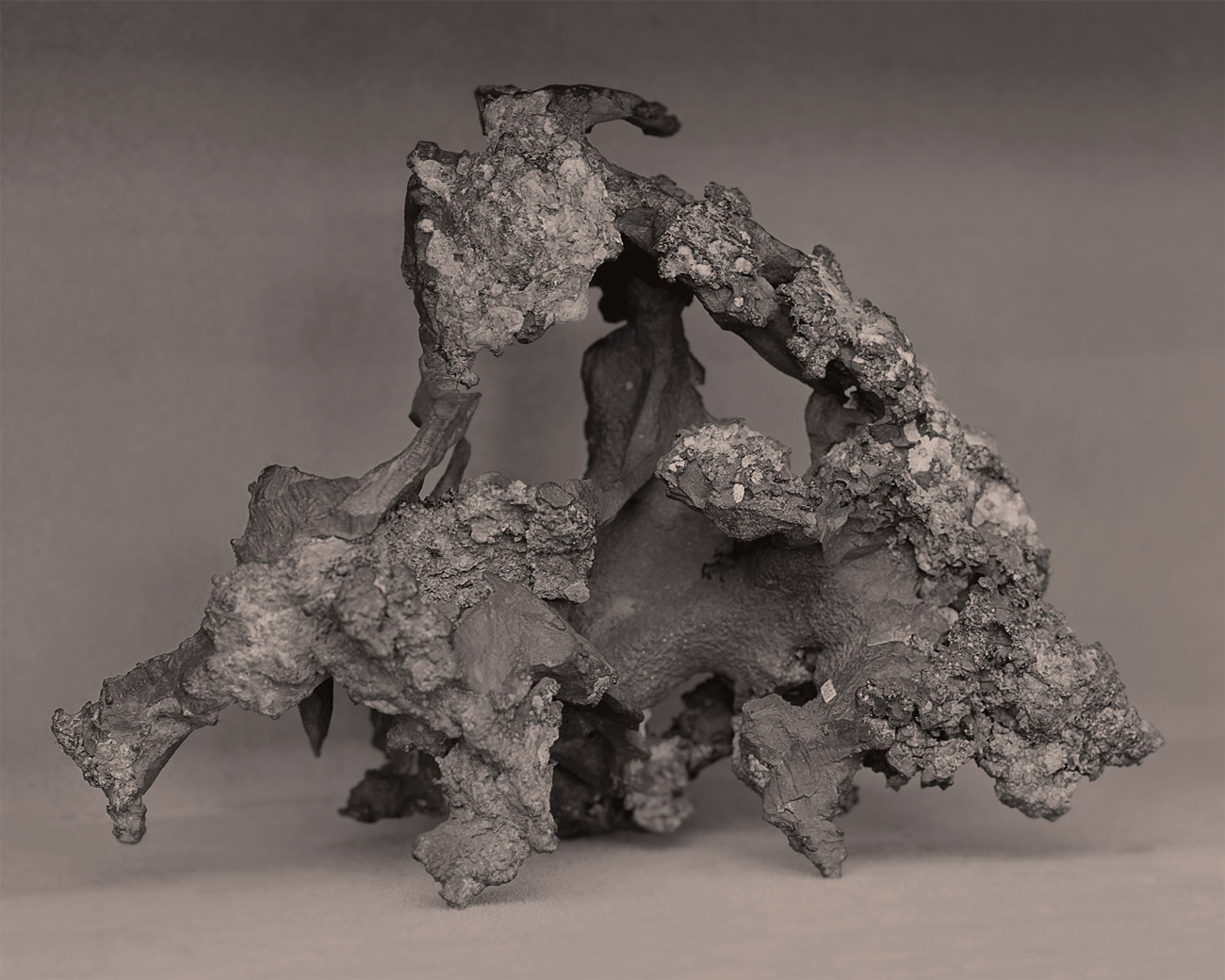

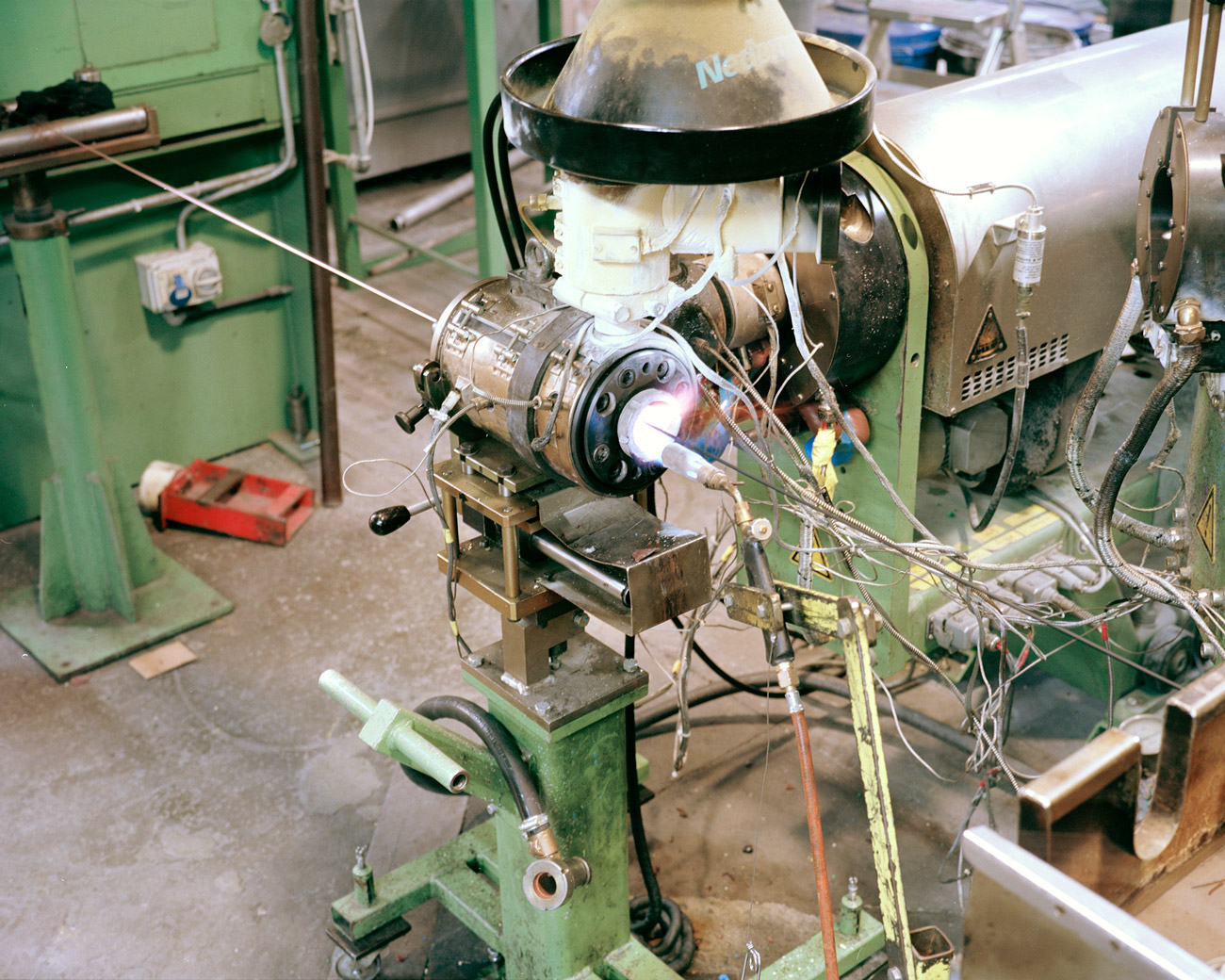

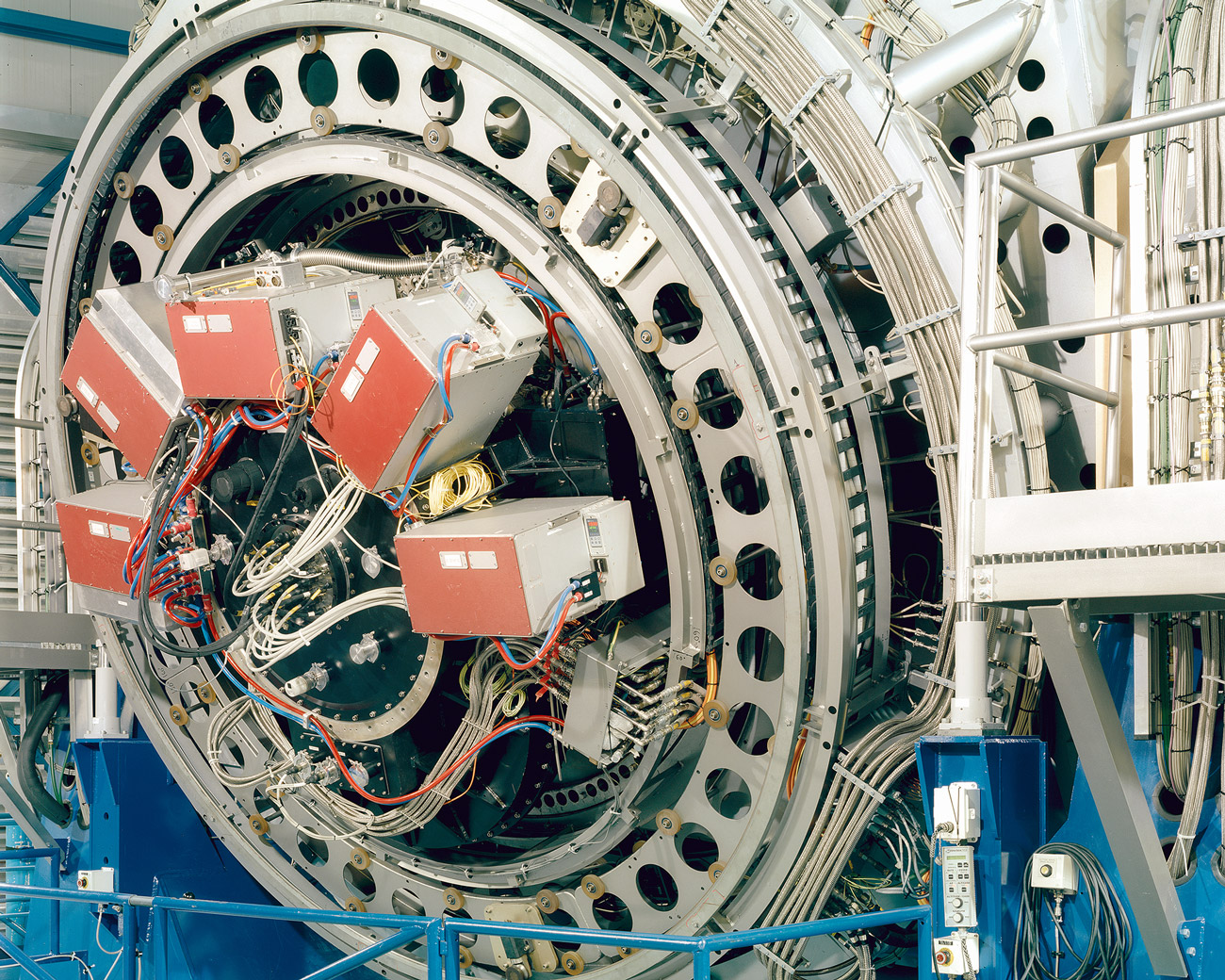

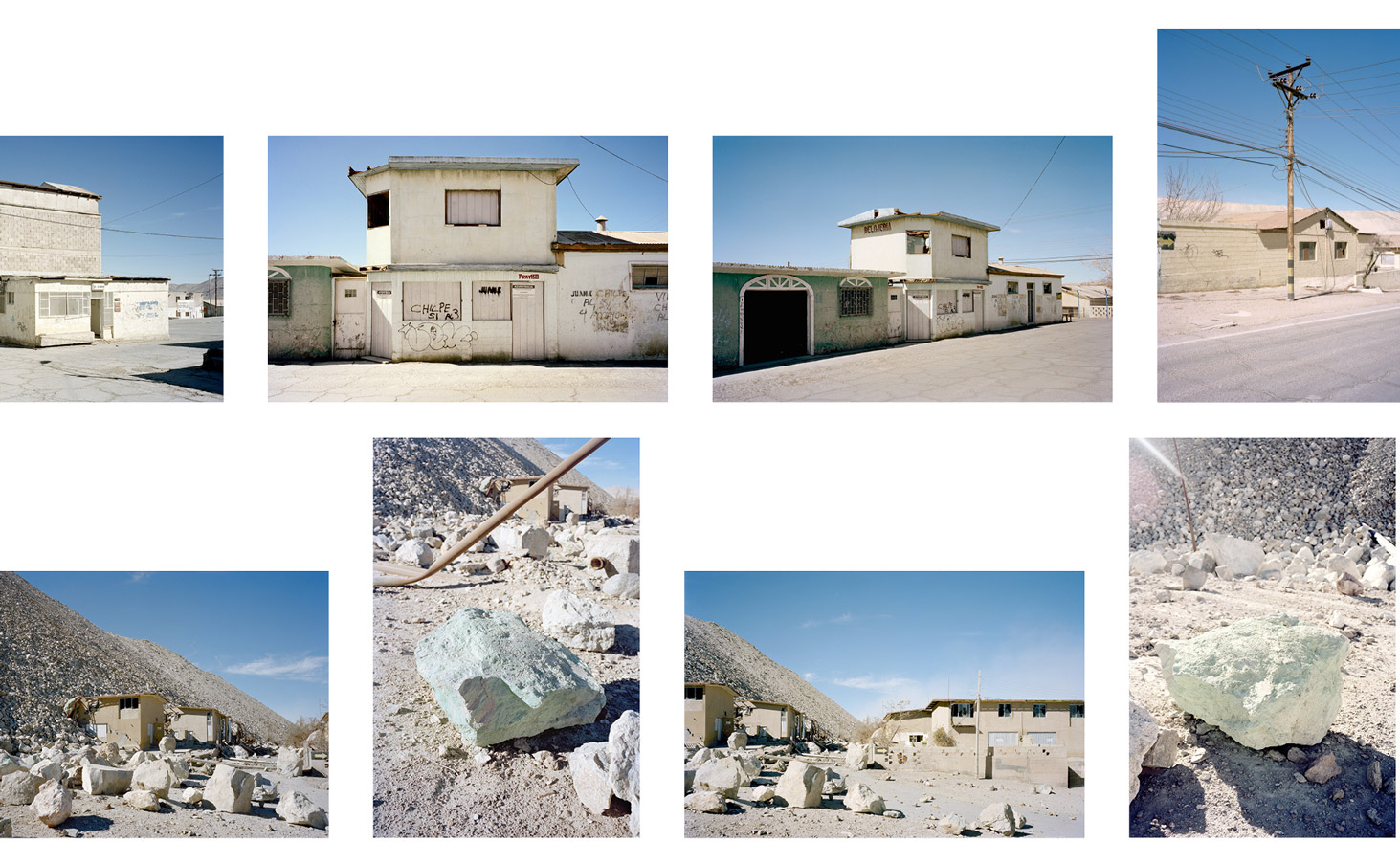

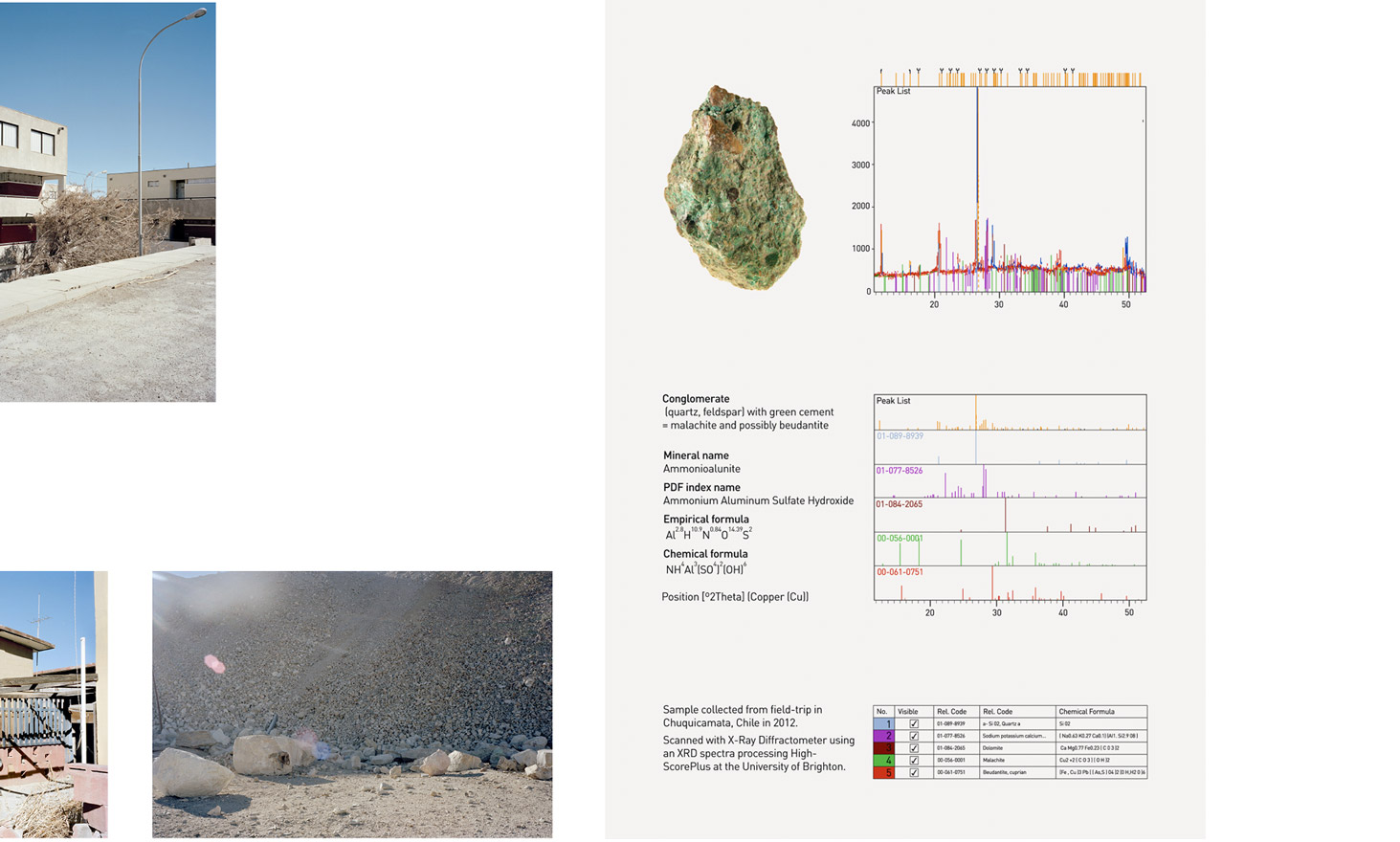

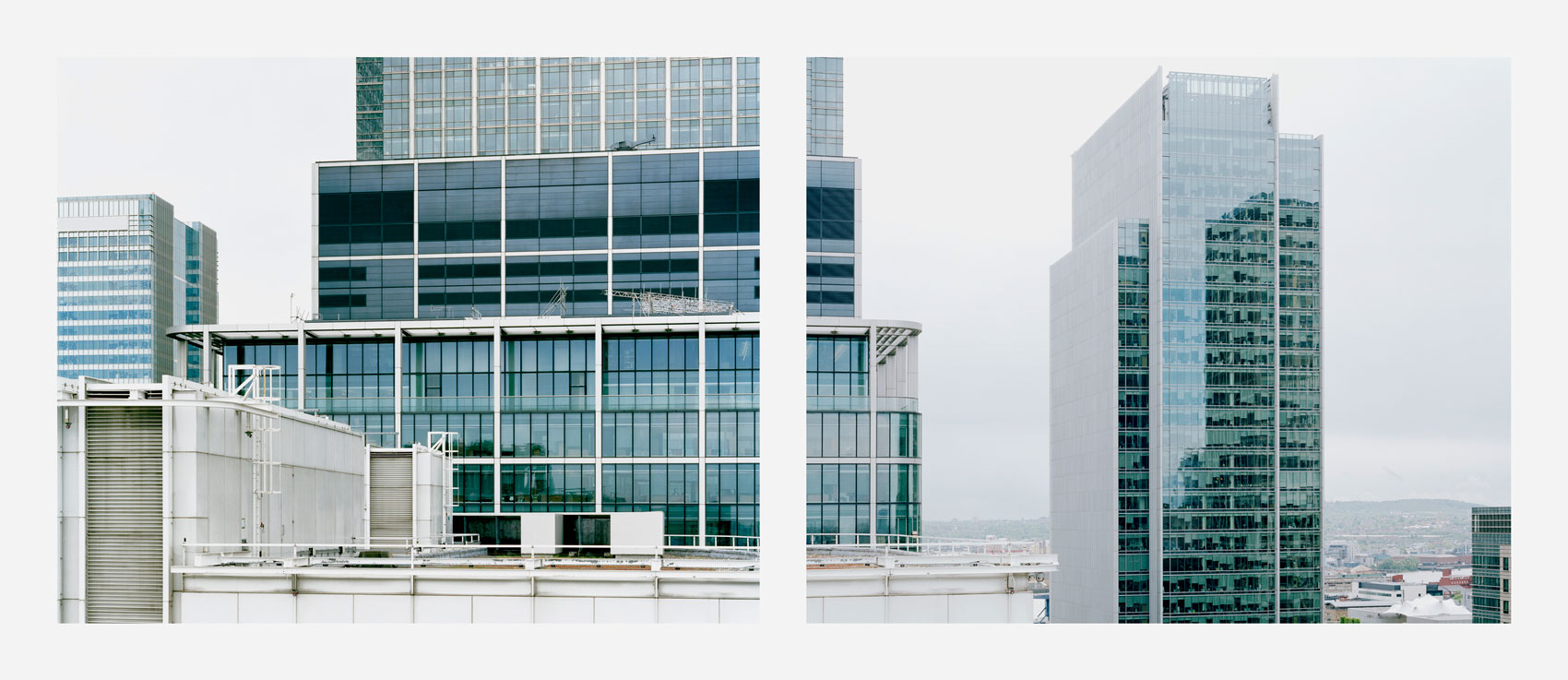

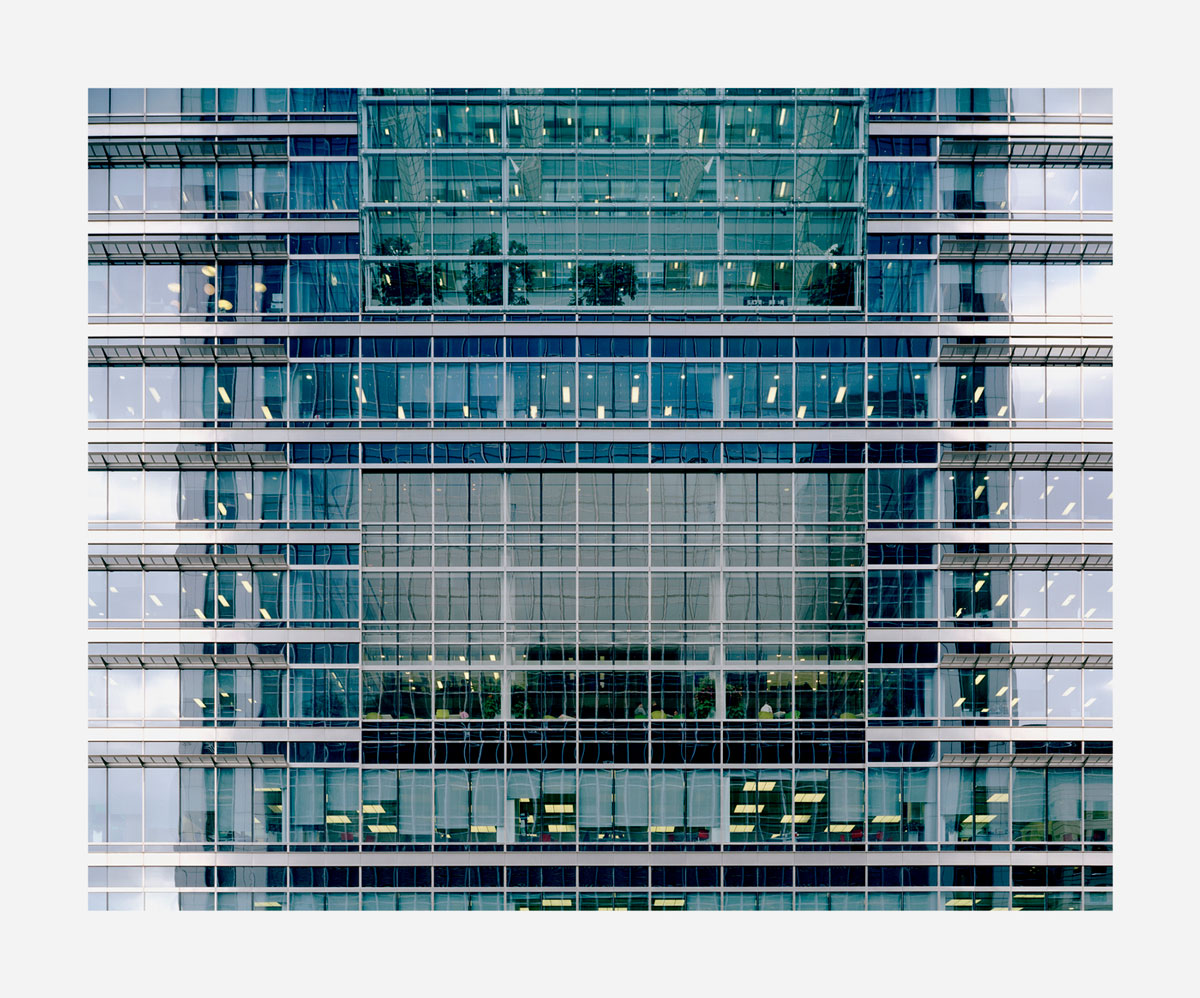

Sudley House houses one of Liverpool’s finest painting collections, which includes major Pre-Raphaelite works. It was assembled by George Holt (1825-1896) through the trade of copper ore and other raw materials that helped boost Britain’s industrial expansion during the 19th century.

Merely looking at the collection gives no indication of how it was acquired or from which capitalist networks it originated, the broader economic and labour conditions in which copper was extracted, smelted and distributed, nor the impact the industry had on the social ecologies of resource exploitation and the powers that controlled them.